The future of messaging: Neutrality and the universal messaging system

The history of technological attention brokerage is the history of the struggle between Facebook, Google, and everyone else. This article wants to imagine something different in the messaging space. Rather than putting messaging revenue in the hands of WeChat, Messenger, etc., the universal exchangeability of messaging could put this potential revenue back in the hands “everyone else.”

I was inspired by a recent article by Yaekyum Lee that projects a possible trend in conversational interfaces. He suggests that while Facebook Messenger might be a great near-term distribution channel for on-demand services or conversational commerce, it’s important to understand that the happy days of large-scale distribution will give way to some growing pains. That is, lower reach and higher costs.

Since conversational commerce is where the idea for this article began, it will make sense to catch people up on it before we jump into universal messaging. But looking forward, my general thesis is that messaging needs an analog to “net neutrality,” especially if it is going to be imagined as commerce.

Conversational Commerce in 2016, and in the future

So what is conversational commerce? As I understand it, it’s the idea that transactions, like the exchange of money for services and goods, will take place through the exchange of messages much like the witty or banal repartee we engage in with our family, friends, colleagues, customers, etc. The idea is pretty clearly attractive. And the friction in transacting fairly limited. A message becomes a medium of exchange, and therefore could circulate as money or commodities, to name a couple classics of circulation.

How does your mobile engagement score stack up?

It’s important that we ask ourselves, “Where do we want this exchange to happen?” The answer to this question basically depends on whether we build our own chat using engineering resources, buy chat as a service, or integrate with some massive messaging app like Facebook Messenger, Telegram, Slack, WeChat, Kakao, or Line, etc. Building a chat in-house is an obvious choice, but it actually takes more resources than you might think to create a fully featured chat at scale. People who have tried to do it tend to agree. On the other hand, I should admit that buying chat as a service is Sendbird’s bread and butter so I am not entirely impartial. But let’s put that aside because it’s not actually the focus of this article. For now, I want to focus a bit on massive messengers and the discussion of conversational commerce that industry folks have built around them.

You might remember that much circulated article by Chris Messina touting 2016 as the year of conversational commerce. If not, it’s over there. His paradigmatic example at the time was the integration of the Uber API into Facebook Messenger, a potential alliance forged in the smithy of tech monopoly. As of August 10th 2017, Uber has already integrated into Messenger using the Uber API. Having sent a message to an Uber driver recently from Oakland airport without Messenger, I admit that the Messenger integration looks like an improvement on the old SMS model.

In conversational commerce, the message is money

Back in 2016, the Uber-Messenger integration obviously made plenty of sense. Facebook Messenger would have allowed Uber to distribute its service to over 1.2 billion users. If a chat message in Messenger equated, as I surmised above, to a hailed ride for Uber, then an exchange of messages would have equated to revenue earned.

If message exchange = revenue, then messaging becomes the medium for transacting. Sound familiar? Money. Money is the material object that represents a value for which we give and receive certain goods and services or as capital and interest.

So in an admittedly extreme form of conversational commerce, messaging is money.

If messaging is money or could become money, then it is extremely important who controls the market because it isn’t a free market in the model of conversational commerce suggested by Messina.

Who controls the conversational commerce market?

So let’s take this a little further, given all the limitations inherent to the assumptions I’m making. Who controls the circulation of messages in Messina’s Uber-Messenger example? Obviously, Facebook Messenger would control the economy of messages, and so Facebook the conversational economy generally. Facebook would set the rules of the market ahead of time and will have the right to change them either according to a contract or freely.

Tapping into a new economy—the fictional Facebook Messenger conversational economy—has large potential in the near term. But how much will it cost in the long-term?

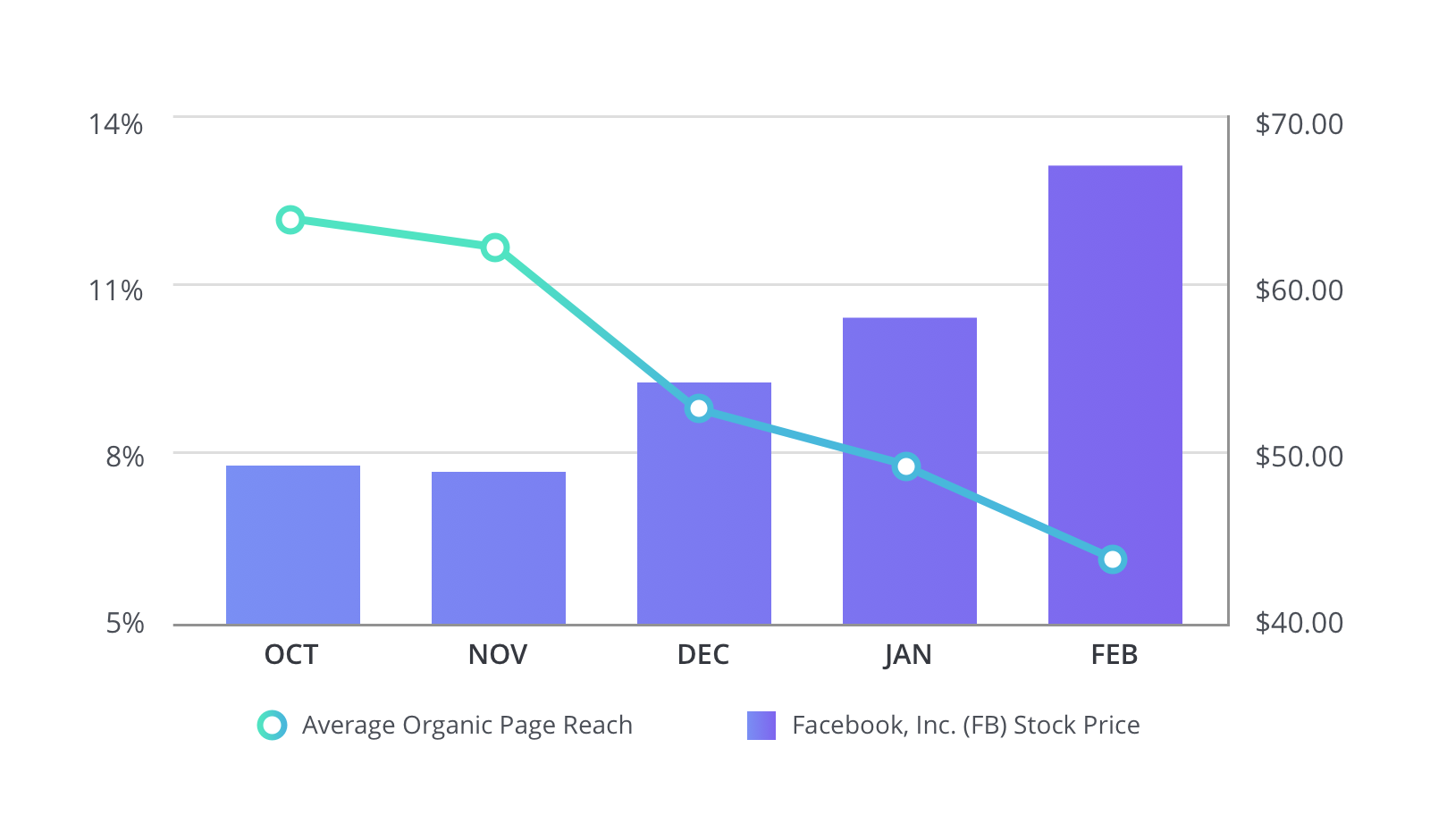

A pattern familiar to those who used to market on Facebook might emerge: as soon as Facebook achieves a certain threshold of businesses using its platform for commerce, they’ll begin increasing costs and restricting organic views. That’s business. This is the pattern that Lee already referenced in his previous article. I’ll reproduce the graph below.

The graph shows the average organic page reach of Facebook’s business pages steadily declining as Facebook’s stock price (and market cap) increases. It’s well known that Facebook deliberately restricted the organic reach of content published on business pages. This required business pages to increase ad spending and therefore the cost to the business.

Heralding the future of universally exchangeable messaging

So back to Messina’s speculation that Facebook Messenger could be a model for conversational commerce. What will the trend in conversational commerce be, given Facebook’s historical behavior? Once Facebook—or WeChat, Line, Kakao, Snap; there’s no need to pick on Facebook—entice enough businesses with Messenger integration, how much will we have to spend to maintain the same reach? Where does that leave us? Dependent on a messenger and at its mercy. We don’t deserve that. So I’ll offer my own declaration, however speculative.

Universally exchangeable messaging is the future. You heard it here first.

Rather than messaging apps being the medium of conversational commerce, let’s make messages universally exchangeable across all platforms so commerce can return from massive messengers to your business environment.

What do I mean by universally exchangeable messaging? Here’s a silly but possible example.

Suppose I am watching the last episode in the 6th season of Game of Thrones on my phone, while taking a walk around Lake Merritt. And my brother is at home watching Luke Cage on Netflix with his laptop. The urge hits. Dang, I need to message someone. Now. From the HBO Go interface, I message @BigBrother: “how much you wanna bet that jamie is gonna have to kill cersei next season?” He receives it inside the Netflix interface, and responds @LittleBrother “what? maybe. what makes you think so? have you heard the music in luke cage? it’s amazing.”

Maybe my brother and I are distracted for a moment. But we’re not leaving our OTT streaming platforms or pulling out another device to check our messenger. Our attention remains within our respective video streams. This would increase viewing hours and engagement, and it would increase potential revenue. And this is just one example among many possibilities.

Universal messaging would essentially mean the free exchange of messages across all environments.

And it strictly avoids messaging exchanges that pretend to be free, but are actually controlled by a few companies who produce messenger apps.

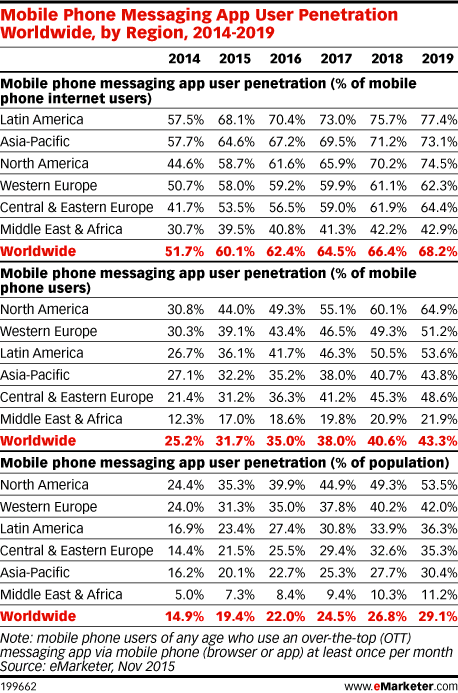

The chart below depicts the penetration of mobile phone messaging app users in a global market. Already we see messaging apps skewing toward the West (i.e. North America, Western Europe), when we take into account more general populations in the second and third charts. That is hardly universality. Just check out the low penetration in the Middle East & Africa, and notice, too, that the chart lumps them together despite the regions being quite distinct.

It is obviously a challenge for companies to penetrate global markets. But if messages meet people where they are, no matter what app or platform, then there is a greater chance that messaging will be used and engage people within the local apps that are most relevant to them.

This is clearly utopian.

Of course, Facebook, WeChat, etc. wouldn’t open their messengers to universal exchange. They’ll guard their users fiercely. They’ll try to keep users in their messaging app by bringing other people’s services to users so that they can keep their engagement high. We have to remember that conversational commerce, though it appears to be a free market, is really just someone else’s app.

And, yet, how many platforms need to be universal messaging compatible before people start demanding that capability from the massive messengers? Messaging utopia is possible.

Are there precedents to universal messaging?

Net neutrality

Net Neutrality is the idea that the internet is a public utility, and that Internet Service Providers (cable and telecom companies) do not have the right to block, hinder, or throttle the internet based on a user’s behavior or choice of application.

It’s important to note that Facebook is not the internet. So when it deliberately reduced the reach on business pages, it had the right to. Facebook is not a neutral platform. In a way, that’s my point.

But net neutrality is being threatened as we speak. The current FCC chairman, Ajit Pai, is proposing the Restore Internet Freedom proposal (ironically named), which would scrap net neutrality and allow ISPs to control the speeds and access to the internet.

It is brave and righteous that Facebook, Google, and Apple have demonstrated support for net neutrality, even though similar arguments could be made against them in an anti-trust case. And I commend them for it.

But, again, if we’re suggesting that messaging is an act of commerce, then universal messaging is as important as net neutrality.

Social sign-in

Services like “social media logins” and “TV Everywhere” appear to be in the spirit of universal messaging, but are not actually.

Facebook, Twitter, Google+, or Github logins–among many others–can be found at thousands of websites and apps. Apps like Tinder highly emphasize Facebook login, whereas phone number verification pales (literally) in comparison (see below).

Social logins have the feel of universal login because you only need to have one account to access another. LoginRadius estimates that 80% of people dislike traditional logins, and 73% prefer to log in using social media (Slide 49 of 65). It’s true. Social login is really convenient, and people love it. But, again, according to estimates in 2015, Facebook dominated the market share of social logins at 61% with Google+ a hop, skip, and a jump away at 22%.

An old but good MailChimp blog article argued against social logins, suggesting that strong UX copy and design could ameliorate your login woes without potentially diluting your brand with a social login. “I was shocked to see,” Aarron Walter writes, “that just 3.4% of the people that visited the login page actually used Facebook or Twitter to log in.” Instead they achieved a 66% drop in login failures and 42% decrease in password resets by improving the UX at their login.

If there are roughly 2 billion Facebook users, it’s difficult to ignore that kind of market share. Like MailChimp, you’d have to balance potential gains in user reach with the strength of your brand. Will you broadcast Facebook at the one page all your users see? Or will you broadcast your brand? If you didn’t know you were using Tinder in the image above, for example, you’d think you were using Facebook. The word, “Tinder,” isn’t even on the page!

TV Everywhere

TV Everywhere is less interesting because it is only universal in name. But it’s a smart idea. TV Everywhere aims to let users log into their paid TV subscriptions from any device. Sounds universal, right? Well, there’s a big caveat. It would have been true, except Comcast, for example, didn’t allow HBO Go on Roku until December 2014 and Sony’s Playstation until December 2016. It was a response by Telecom and ISPs to control their markets, which Direct To Consumer (DTC) content via Over The Top (OTT) platforms, like Roku and Playstation, threatened.

Paradoxically, these two apparent efforts at greater universality are actually dominated by very few companies. Well, maybe it’s not so strange. People have been touting universality for a long time, while only actually considering a very few. For a reference, see the internet when it was only in English.

Conclusion: the global economy is the messaging economy

I have to admit that there are limitations to this because messaging apps are not purely communication or commerce channels. Facebook makes money because they sell audience attention to advertisers. Same with Google. In fact, Fortune reported that 90% of the ad growth in 2016 belonged to Google and Facebook.

So it makes sense that we might be afraid to expose our internal messaging system to the open messaging market before Facebook or Google, or whatever “attention broker,” limits organic impressions. Or before they open their company’s ad market to other competition. The solution, if it has to do with conversational commerce, has to be a balance between both internal messaging and access to large-scale attention brokers.

So what’s the point of this speculation? Pointing out that utopia does not lie with massive messengers. It depends on being able to keep your conversational commerce within your platform. Messaging utopia is possible!

—

A version of this article appears on IT Pro Portal, published September 12, 2017.